Why This Archive?

Note that all materials on this site are copyrighted and may not be reproduced without the author's and/or artist’s permission.

Notes from Jan Rindfleisch, Euphrat Museum of Art director (1979–2011)

This archive is presented by cultural workers, academics across disciplines, colleagues, activists, and others who enjoy sharing art and ideas. It is a living history that documents, honors, discovers, and connects with unique aspects of the Silicon Valley and Bay Area cultural/educational scene today.

Website development is the result of concept enrichment and ongoing collaboration with arts advocates/editors Nancy Hom and Ann Sherman and designer Samson Wong.

Silicon Valley has been a crucible for start-up organizations, including those in the arts. Start-up arts organizations, such as the Euphrat Museum of Art, are an important cultural resource, a stimulant for creativity and innovation. Many individuals and organizations have not had the time or the resources to record their accomplishments, ideas, and insights, particularly in the decades before computers and the widespread use of the internet. Our intent is to provide extra information to assist others who may be researching these past decades to view progression of artists, ideas, innovation, and organizations in Silicon Valley. Many of these artists and groups are flourishing today, tilling new ground. Our updates and dialog can provide continuity, encouragement and opportunity, opening new doors for future artists and arts organizations.

The importance of Euphrat archival work can be seen in the renaissance of artist Agnes Pelton (2020 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art) which has its background in the extensive Staying Visible project, exhibition, book, and work with the Smithsonian Institution. The book’s opening essay follows.

The Importance of Archives, 1981

Introductory essay, Jan Rindfleisch, 1981, for Staying Visible, The Importance of Archives, produced in conjunction with Euphrat Museum of Art exhibition. The concepts and questions are relevant today.

"It takes work, lots of it, to keep artwork and artists visible… Talent alone, 'good work,' is no assurance of anything."

- Michael Bell

Purposes

This project began two years ago. Its purposes were to search California and national archives and find out what information was already available about several neglected artists; to collect more information; to make a challenging and visually exciting gallery show from the project; to put the newly acquired information in the archives (so that others would have the chance to review this work, and find something more than we found) — and to publicize the importance of "saving stuff" in keeping an artwork, and an artist, visible.

We have had our ups and downs. The stories are many. They tell of some of the problems of research and recognition — why A is remembered and B is not.

I approached The Archives of California Art at The Oakland Museum, and I started working with Michael Bell, then Registrar/Cataloguer for the Oakland Museum Art Department; with George Neubert, then Chief Curator for Art at The Oakland Museum; and with three graduate students from San Jose State University. Within eighteen months, problems with money, families and jobs changed the working group almost entirely. The Oakland Museum was in financial straits as were so many other public institutions in 1980, and the graduate researchers themselves faced a variety of pressures.

While some researchers were forced to leave, others appeared on the scene, and I increased the number of artists to eleven in order to include contemporary San Francisco Bay Area artists whose media, backgrounds, and art-world ties were different from mainstream art and/or from each other. The diversity of artists is important. It awakens us to the variety of what can get lost from the records: a portion of a famous artist's life or work; the historical/critical significance of the artist, once "in favor," who has since been neglected by critics and curators; the life and work of the isolated artist, the artist with several careers, and the non-traditional artist whose visibility is subject to the vagaries of what a fine artist is and is not.

The diversity of researchers is also important. The new researchers for these additional artists were not all graduate students but were connected to the artists in various, and often more intimate, ways: artist colleagues, art historians, close friends, co-workers, mentors, or admirers from other fields. Each researcher had a different relationship with her or his artist. Each researcher had different motivations, commitments, job pressures, and a different approach and view of their involvement. These factors invite consideration of the human element of decision-making in the arts. The list of great artists, which we learned in elementary school or in art history classes, did not drop from heaven but was the result of decisions by such real people.

At first the researchers often asked me: What kind of "stuff" do you want? What gets written? What gets saved? I responded with a list of facts and possible items, but left many decisions to the artists and researchers. I like surprises and I wanted connections to come naturally rather than be artificially imposed. I imagined myself inundated with old photos; stacks of letters, postcards, birthday cards; memorabilia, from palettes to visual aids around the studio; bills, contracts; rough drafts; posters, mailers, reviews; interviews, taped and transcribed; sketchbooks and journals of artists and researchers; the standard resumes; and so on and on. I already knew that the painter Barbara Rogers was going to present me with a box of old gallery announcements she had saved.

Philosophical Guidelines

Our philosophical guidelines were simple: "Archives save everything; others decide later what is important."

But we soon discovered the problems of archivists: How much time, space, effort, and money were we practically willing or able to invest? Furthermore, many artists, and even researchers, were not willing to give original papers to the archives (at least not yet), but were willing to have these copied. We soon had tables full of photocopies and tape duplications.

Also, although archivists may want to save everything, artists don't always want to give everything. Some artists do not want their personal letters to go anywhere or be copied. Some do not want certain "personal" facts related, even though such facts might explain much about their work. While some artists are candid, others are afraid to be quoted or speak their minds. Marjorie Eaton, an artist represented here, says she once gave a museum a list of people she thought it would be proper to acknowledge as influential. A critic twisted this gesture and said Eaton should make up her mind about whom she wanted to copy.

The difference between art, archival material ("papers") and memorabilia and the significance of their cohabitation in archives were not always clear to us. Preliminary drawings, sketchbooks, taped interviews, and photographs are put into many archives. But "preliminary" drawings, sketchbooks, and photographs are often considered finished works of art, and taped interviews can be performance art. And what about the decorated envelope sent from artist Bettye Saar to Mildred Howard? The watercolor Easter card sent from Consuelo Cloos to Marjorie Eaton? The calligraphic poem sent from Jim Rosen to Fay Evans? How about the lotería cards Carmen Lomas Garza's mother made, clearly an inspiration and source for Garza's lotería etchings? What are the advantages, disadvantages, and implications for the future life of these things, housed alongside documents in an archive? (And if some art is included, why not all?)

Underpinnings

It was exciting to discover, collect, save and share … to put things in archives is to preserve more than we know. Art history is based on facts, and archives often hold "the proof." They are the "underpinnings" of our statements.

We felt an importance in our work. Paul Karlstrom's [West Coast Area Director, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution] foreword underlines this feeling. He wrote that the goal of archival activity was "to fill in the many gaps and omissions resulting from contemporary curatorial and critical selectivity."

Karlstrom voiced our feelings again when he wrote that many serious California artists complain that they are "locked out" of an art establishment network; that there is an absence of a literature devoted to contemporary art communities in California.

Geographical bias, however, is not the only reason why many artists in California feel they are "locked out" of the art establishment and "written out" of history books. Many sense exclusion because of race, gender, nationality, religion… or individual quirks. Motivation, for many of the researchers and artists, was the chance to add to art history.

This is important, that we can add to art history and even become a part of it. Art people can make their own archives: save announcements and letters, take the step from boxes of papers to the two-drawer filing-cabinet system, progress to taking photographs and making audiotapes.

Not only can art people "save their stuff," they can record other art people. They can speak to the historical consciousness and responsibility of the art community and the local community…

… often quite imaginatively. Patricia Rodriguez artfully documents herself, Garza, and other Chicanas by combining plaster masks of their faces with some of their memorabilia.

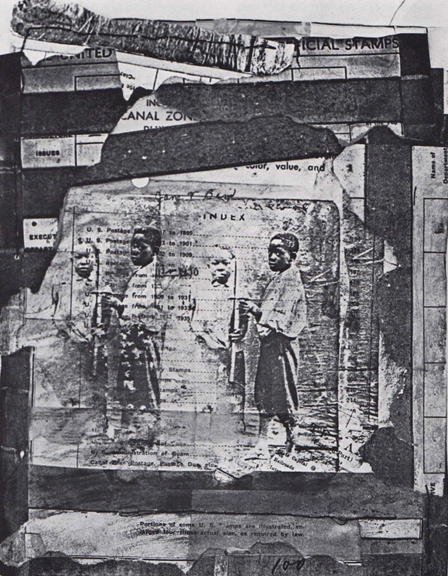

Garza saves and pays tribute to the art of her mother in the lotería etchings. Rosen writes a poem to Evans and letters to museums to have Evans's work purchased. Mildred Howard creates historical collages.

Katherine Huffaker and Therese May collaborate and record each other's art by making more art. Margaret Stainer is a non-stop letter writer and keeps a journal of her research on Agnes Pelton.

During their lives, art people need to attend to art and papers, to protect them from flood, fire, chaotic housekeeping, and more deliberate destruction; later these items need to be protected from unknowing or uncaring relatives, friends, and/or neighbors. It behooves us to keep our "papers" and art in order. As Beatrice Wood says about invoices (see her interview, page 13), it is important to keep daily business in hand or we will not know freedom…

"Laziness is no excuse," Michael Bell used to say to me. It takes work, lots of it, to keep artwork and artists visible. The necessary components are time, money and a strong belief and commitment by someone to get an artist in a history book, a museum collection, or a major exhibition. Talent alone, "good work," is no assurance of anything.

Yet how many of us are saving our correspondence? How many keep a "three-line" diary like Beatrice Wood?

Questions Continue

We have learned much, yet the questions continue.

We were putting things in archives. And I wondered who else puts things in…and what kinds of things are not accepted, not considered worthy of documentation. Once quilts were not accepted as a fine art form. How well are quilt makers documented in various art archives today? What about cartoonists or commercial artists? or Leila Macdonald who made a robe from fabric scraps? Selectivity is a critical issue. In order to understand the art of any period, all the art activity must be documented, not just that of a few people; a wide-open range of papers must be saved, not just artists'.

Karlstrom told me that the Archives of American Art at the De Young Museum in San Francisco did not have a "master list" of who was to be included; that they received recommendations from a network of consultants; that they "tried to distort history as little as possible;" that they sought out information. But how much effort goes to seeking out diversity? How many artists (especially if they are not attached to an institution) know about archives? How many get their visual products documented and secured?

More information needs to get out about the existence and uses, the importance of archives. In addition to the state and national archives, there are many art archives around, with many purposes. In the San Francisco Bay vicinity, examples of smaller archives are the Contemporary Art Archives at La Mamelle, Inc.; the growing archives at the Galeria de la Raza; the personal archives of Jan Butterfield, Associate Editor of Images and Issues, who is writing a book on emerging California artists; the files of gallery artists at the Center for Visual Arts, Oakland; the Women Artists' Archives at Sonoma State University; the library files at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Awareness of these and other archives presents us with a dilemma of where we might deposit our research materials, since we qualify in many areas. Touch of the "real thing" is important — this is possible at the Archives of California Art. However, discussions between researchers, galleries, artists and other potential donors have not finalized the placement of primary source material. Of course we will coordinate with all archives for which this material is a vital addition. We are still learning how different archives cooperate with one another, the tug-of-war between "pride of possession" and the realization that no one has the space to hold everything or receives consistent "A" grades on preservation and accessibility.

Questions about information glut, creative filing, problems and benefits of photocopy machines, use of computers, varieties of researchers' styles, the importance of touching "the real thing" versus using microfilm, the importance of proper care of primary sources, the attitude "the art work stands by itself" without label or context — these questions are too large to confront here, but demand continued discussion. We confronted them. One way or another they touch the future visible life of every artist in this book.